We head up the mountain on our first rotation in the next day or two. Given the sporadic nature of internet here at base camp, I am going to post this right now while I appear to have a window.

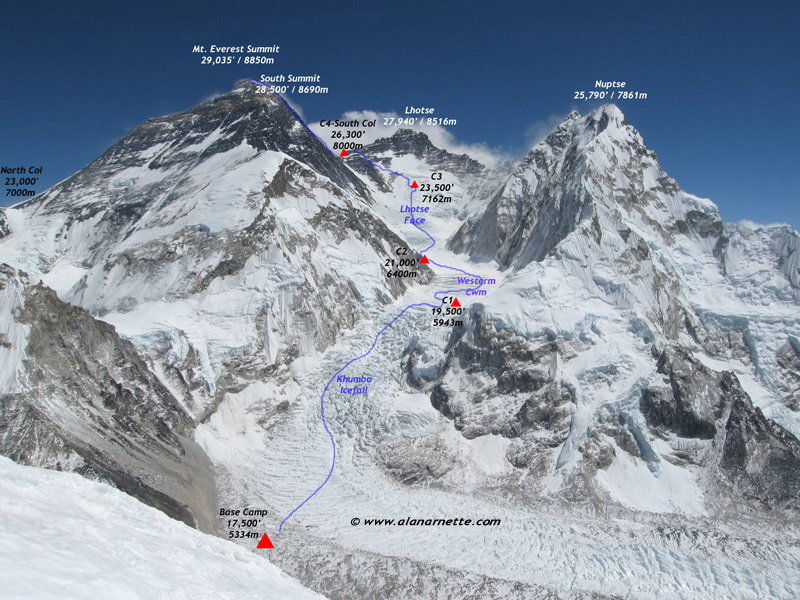

As described previously, this rotation will involve climbing through the Khumbu icefall to Camp 1 at 19,500 feet, spending three nights there to acclimatize, climbing further up Everest’s so-called “Western Cym” to Camp 2 at 21,000 feet, spending two or three nights there to further acclimatize, then descending back down to base camp.

Of all of this, getting safely through the icefall is most prominent on our minds. A maze of frequently shifting ice blocks and crevasses, subject to constant avalanche threat from above, it is one of the most dangerous parts of an Everest climb. It is also one where climbers have little personal control over the risks they face. Other than having the technical skills and physical ability to move quickly, it either is your day or it isn’t. We expect our climb through the icefall to take around six hours, (substantially faster when we descend a week later). On subsequent rotations we should be able to shave our ascent time to closer to four hours, as we will be better used to the altitude and more familiar with the route.

On the positive side, the odds are in our favor. The reason we are starting at 3:00am is so we can get through most of the icefall before the sun’s rays increase the likelihood of an avalanche or a mammoth ice block, (called “serac”), toppling over on us. Also on the positive side, many experienced mountaineers view the icefall as one of the most uniquely beautiful places they have ever climbed through. It is other-worldly, with an ever changing constellation of ice towers, deep crevasses, and myriad shades of blue ice.

Two days ago, we climbed about a quarter of the way through the icefall and back to get ourselves “dialed in”. Here is a photo from that outing:

And here is another:

Things will get more dramatic higher up.

While I don’t like the risk of climbing through the icefall, I have come to terms with it. It is the only way to gain access to the upper reaches of the Everest, (from the Nepal side), and generations of climbers have faced this same decision. It is one of those risk/reward trade-offs we all make in our lives, in various forms. Our team will navigate the icefall six times on our climb; three times ascending and three times descending. Each time I am through I will breathe a sigh of relief. The last time I am through, on my way down after having hopefully summited Everest, I will breathe a sigh of extreme relief, deep satisfaction, and gratitude for safe passage.

Once above the icefall, we will be in a vast glacial canyon called the Western Cym, with Everest and its neighboring peak Lhotse towering above us. While the route through the Cym from Camp 1 to Camp 2 is demanding, and will involve some dramatic crevasse crossings, the risk factor is far lower than the icefall. I have spent my entire life visualizing the Western Cym and look forward to experiencing it in person. We will likely be feeling miserable due to the altitude, but I’ll still be glad to be there.

OUR TEAM

I owe you some detail on our team. We are seven climbers (aka “members”), two lead guides, and an expedition “Sirdar” who oversees a crew of fourteen climbing sherpas and eight additional staff.

Before describing the individual team members, I need to note that the climbing Sherpas do the real work of the expedition. They arrive weeks in advance to carve base camp out of the glacier, and – most importantly- make numerous trips through the icefall and above to set up and provision our high camps. They are all extremely strong climbers, with numerous Everest summits among them. A handful of the strongest will climb with us the night/day that we attempt the summit.

As mentioned in a previous post, our team is strong relative to many on the mountain. All seven members have climbed multiple high peaks and prepared relentlessly for years, As you would expect, there are additional common denominators. Everyone is driven, everyone has subjugated their personal and family lives to the goal of climbing Everest, everyone is in strong physical condition, and everyone is used to pushing their bodies to the limit while enduring extreme physical hardship. Meanwhile, our lead guides, Sirdar, and climbing Sherpas are among the best in the business.

Some quick profiles, (note: exact ages are informed guesses):

JOSH: Josh is a former Army Ranger who founded a successful media company focused on college football websites. In his early forties, he has a wife and two young children at home in Indiana. He is in exceptional physical condition, naturally athletic, has strong climbing skills, and is supremely motivated. I can’t picture a wall of any sort that Josh would be unable to get over or through.

TONY: Tony, in his late thirties, runs a solar company in Ohio. He says he got fired from his first eight jobs so figured he’d better start a company of his own. Several years ago, in his first foray into mountaineering, Tony signed himself up for a program that involved thirty days of extreme outdoor leadership training in the mountains of Argentina, followed by a climb of Aconcagua. Tony told his group that he would summit Everest someday and everyone laughed. If he is successful on this climb, he intends to call every member of that group and tell them that he did it.

Tony’s wife Raissa trekked with us to base camp. Her initial intent was to climb with us on our first rotation up to Camp 2. A former nationally ranked swimmer in Brazil, she trained hard for this over the past year, including a 5 day mountaineering course on Mt Baker in the Cascades tailored to help her get ready for the icefall. After arriving at base camp, going on some acclimatization hikes, and doing some training in the lower icefall, she decided to take a pass on the first rotation. Raissa headed home yesterday and we all gave her huge hugs as she left base camp. She added a lot to our group, (including keeping Tony more or less in line 😊), and we will miss her.

CHASE: Chase is 18 years old and has spent the past couple of years climbing big peaks all over the world, (with some of the best guides in the world). His initial hurdle was that all the guiding companies told him he was too young to go, but he managed to get past that and is now on a roll. In recent examples, in the middle of Covid when most mountains were shut down, he managed to climb Mt Kenya in Africa and Ama Dablam, a 23,000 peak here in the Nepal. The thing that blows my mind is that, right after Everest, he plans to climb Makalu (near Everest, another of the highest peaks in the world), and then, right after that, K2 in Pakistan, (the second highest peak in the world, more difficult and dangerous than Everest). Chase is a very skilled climber and handles himself well in a group of people much older than him. After the next set of climbs, he hopes to follow his father and sister in attending West Point, and to build a career around flying helicopters.

MARK: I alluded to Mark in a previous post. In addition to climbing six of the “Seven Summits” (ie: the highest mountain on every continent), he has also skied the last latitudinal degree to both the North and South Poles. In his mid fifties, Mark lives in Seattle. He was the Chief Technology Officer for a software company that was recently acquired by a private equity firm. When they tried to convince him to stay on, he explained that he couldn’t because he has more mountains to climb. Mark was on Everest three years ago but had to descend relatively early in the climb, from just above the icefall, due to some altitude-induced intestinal complications. He is eager for another shot.

BOB: Bob is, (ahem), my age. He is a surgeon in Arizona, has climbed six of the Seven Summits, and is determined to make Everest the seventh. Bob is nothing if not determined. He casually mentioned to me that it took him four tries on Aconcagua, but he kept going back until he succeeded. Similarly, this is his third attempt on Everest. Two years ago, he got to Camp 2 before injuring his shoulder in a fall and having to descend. He also mentioned that this time he has arranged for a personal Sherpa to climb with him on the upper mountain starting at Camp 2. I’m not sure exactly what that entails, but I look forward to finding out.

THOMAS: Thomas is, (ahem, ahem), also my age. He founded a hedge fund focused on arbitraging closed end bond fund yields. During our trek to base camp, he explained exactly what this means, and I had it clear in my head for a few fleeting days. The fund did well, and Thomas recently converted it to a family office to lighten regulatory compliance burdens. He also converted his role to Chairman, so he could spend more time climbing mountains and traveling the world.

When you ask Thomas about mountains, he leads with describing long hikes in the high peaks of the Adirondacks, or the Presidential Traverse in the White Mountains, or a medium sized mountain in West Africa that he found a guide to take him up. Only when you ask additional questions does it emerge that he – like most of our group – has also climbed six of the Seven Summits. The driving force for Thomas appears to be appreciation of mountains of any size, and for all aspects of climbing them. He is superbly fit, very organized about how he approaches climbing, and has been right up with the front of our group on all the acclimatization hikes and climbs.

BEN JONES, (Lead Guide and Expedition Leader): Ben, from Jackson, Wyoming, is a mountain guide straight out of Hollywood central casting. As one of the top guides at Alpine Ascents, he guides on peaks all over the world. This is his 10th season on Everest. Son Will and I climbed with Ben in Antarctica two years ago, so I was already familiar with his deep technical competence, disciplined approach to leading a group, and direct, “suffer no fools” style. One of the things that attracted me to this Everest expedition is Ben’s strategy of being in no rush, letting other groups push to get up the mountain first, and patiently waiting for the optimal window to go for the summit. We are in very good hands with Ben.

JANGBU SHERPA, (Lead Guide): Jangbu grew up in Nepal, worked as a trekking leader, then became one of the early few Sherpas to become an internationally certified climbing guide. In 2011 he summited Everest largely by himself: arranging his own gear, carrying all his loads personally from camp to camp, and climbing alone. He has since summited Everest as a guide multiple times and leads climbs all over the world for Alpine Ascents. While his home is now Seattle, he returns to Nepal every year to climb Everest and other peaks. Jangbu has a warm, outgoing personality and is a natural people person. Everywhere we go on Everest, Sherpa guides cry out greetings and want to stop and chat with him. Everyone knows him. I feel like we are on Everest with one of the mountain’s favorite sons. Because we are.

LAKPA RITA SHERPA, (Expedition Sirdar): There are few people who can eclipse Jangbu’s profile on Everest, but one of them is Lakpa Rita. Lakpa is a Nepal climbing legend. He grew up in the Khumbu village of Thame, walking three hours round trip every day to attend the nearest school, and went on to become one one of Nepal’s most famous Sherpa guides and mountaineers. Lakpa has summited Everest 17 times. When some of our team members went into a climbing store in Kathmandu to pick up last minute gear, they encountered a wall of “Lakpa Rita signature outerwear “ with Lakpa’s name and photo on all the clothing tags.

When the avalanche in 2014 killed 14 Sherpa in the icefall, Lakpa was among the first people on the scene to attempt a rescue. Many of the dead bodies he dug out of the ice were from his home village of Thame. After that, Lakpa promised his wife that he would never enter the icefall again. He has since focused his Everest efforts on playing the role of Expedition Sirdar, overseeing all logistical aspects from base camp. He continues to guide other peaks internationally for Alpine Ascents.

I met Lakpa Rita two years ago at Vinson base camp in Antarctica. Will and I had just been dropped by a Twin Otter airplane and were struggling to set up our tent in the extreme cold. Out of nowhere, someone not from our group came over and quietly asked if we needed help. Nanoseconds later, our tent was up. Lakpa Rita then politely wished us good luck on the mountain and walked off into the minus 40 degree evening. I turned to Will and said: “we have just been in the presence of a mountaineering god”. Because we had.

So now I am on Everest with Lakpa Rita. It is hard to put into words the respect I feel for the competence, humbleness, good nature, and quiet dignity that this man exudes on a daily basis.

Here is a photo of Lakpa and me taken a couple of days ago outside our dining tent. I have my mountaineering boots on because we were about to head off on a dry run climb into the icefall.

OFF WE GO

And now the real climbing starts. After we turn on our headlamps and head into the icefall, it will be six or seven days before we return to base camp. We will be leaving internet access behind, so I will next post when we get back. I should have plenty to describe.

I am feeling fully prepared and ready. My body continues to be handling the altitude well, and I have been performing well on the acclimatization hikes and climbs. It is hard work, but that is the name of the game. A few of my technical climbing skills, while objectively as strong or stronger than most of the guided climbers on the mountain, are not yet at the level I personally want. But I am closing in on it, and I will get there.

There have been several Covid cases in base camp, with the climbers being evacuated to Kathmandu. At the moment, this feels like a manageable situation, particularly as the climbing teams operate very independently from each other. That said, things can evolve in unexpected ways. Fingers crossed on that front.