Reader alert: this is going to be a long post.

When we left basecamp over a week ago on our summit push, we were trying to thread a needle. For the past five days, the remnants of Cyclone Tauktae had pummeled the upper reaches of the mountain and made the summit inaccessible, keeping us waiting at base camp for things to clear. Meanwhile, unbelievably, a second cyclone, named Yaas, was forming in the Bay of Bengal and threatening to impact Everest as well, but it’s exact track and impact was not yet clear. So we headed up the mountain, hoping to pull off a summit attempt between the two storms.

THE ASCENT

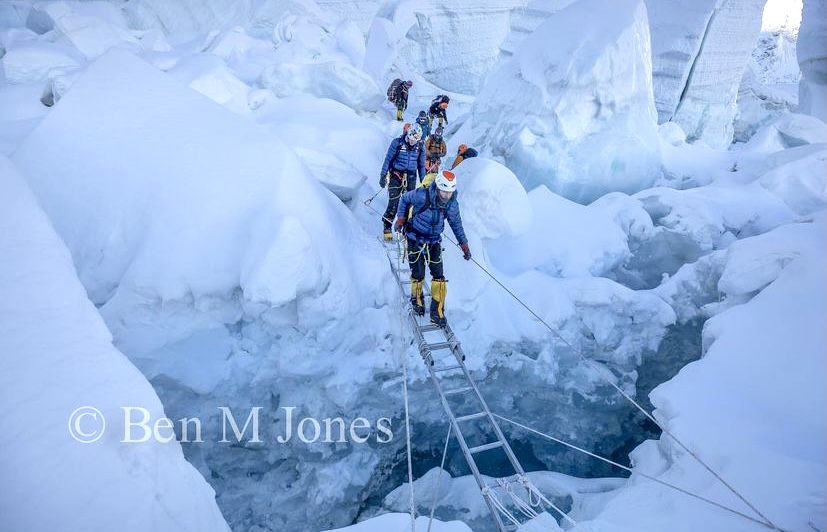

On our first long day, we climbed the now familiar route through the icefall to Camp 1, then kept going up the Western Cym to Camp 2. The icefall had changed notably since the first time we climbed through it a month ago, with ice bridges having melted out, crevasses opened up, and sections of the route having been re-routed to accommodate collapsing ice towers and the ever moving jumble of ice.

We had planned to take a rest day at Camp 2 but, with an eye toward the ever changing weather forecast, we decided to keep moving and climbed the next day to Camp 3 at 23,500 feet. We had been there on our second rotation but this was our first time spending the night. It is in a spectacular location, carved out of a shelf half way up the Lhotse face. More than one person has slid to their death by not being super careful moving around unroped outside their tent. We were super careful.

Here is a photo taken at Camp 3 shortly after we arrived. Those are our red tents in the foreground.

The next day, we kept on pushing and climbed up to Camp 4 at 26,000 feet. While this was another extremely demanding day, it also was exhilarating. The route starts out with some steep ice climbing up the Lhotse face above Camp 3. Then it climbs more gradually across the face, over the so – called “yellow band”, and up to and over the “Geneva Spur”.

If you are a climber or student of Everest, these geological features have an almost mythical significance. They certainly do for me. A bit like features on the moon; in another world and previously viewed only in photographs. When anticipating this climb, I promised myself that, no matter how exhausted I was, when I got to these places I would pay attention and absorb the fact that I was actually traversing them. I was indeed exhausted, but I kept my promise. I was able to look around, internalize being there, and lock in the experience for my memories.

The yellow band, by the way, is a prominent rock layer that cuts across the entire south side of Everest. It marks the beginning of the so- called “death zone”, the altitude at which the human body, if it stays there for a prolonged period of time, starts deteriorating rapidly and losing functionality. Climbers try to spend as little time in the death zone as possible.

Here is a photo of Chase and Josh between Camps 3 and 4, angling up toward the yellow band and Geneva spur.

And here is another of the upper reaches of Everest, taken from the top of the Geneva spur. Our anticipated summit day route goes up the snowy “triangular face” on the bottom right, gains the right hand ridge about half way up, then follows the ridge line to the top of the world. The snow plume off the summit tells you it was windy up there.

This is a view of Everest that you don’t see a lot, unless you are thinking of climbing the southeast ridge, in which case you have studied photos of it with reverence. For me, gaining this vantage point in person was another “I can’t believe I am really here” experience.

To review the weather needle we were trying to thread: As we approached Camp 4, the remnants of cyclone Tauktae had cleared out three days previously, creating a brief window of clear weather. This created a summit opportunity for those teams that had moved up the mountain a week ahead of us and dug themselves into Camp 2 to wait out the storm. Meanwhile, the weather forecasts were united in the view that Cyclone Yaas was also heading toward Everest and would bring winds and snow to the mountain starting that afternoon. What the forecasts differed on was exactly how strong the winds and snowfall would be.

Considering these forecasts, and also factoring in how late in the season it was, many of the teams remaining on the mountain cancelled their expeditions. A few others decided to wait even longer at base camp to see if a final, extremely late weather window presented itself post Yaas. We decided to give it a shot on the front end of Yaas’s arrival.

Our weather forecaster was suggesting that, as Yaas arrived on May 25 and 26, the winds on the mountain, while significant, would be in ranges reasonable enough to permit a summit attempt. This is what we were betting on, and why we were rushing up the mountain to be at Camp 4, in position for a summit attempt on May 25 (departing the night of the 24th). This would also give us the option to defer our attempt to the 26th if needed.

All through the climb from base camp to Camp 4, I was feeling good relative to any reasonable expectation. My body was dealing with the altitude really well. I was working harder than I have ever worked on a mountain, and having to summon extreme will to put one foot in front of the other to keep moving upward, but I was feeling strong and right in the zone I wanted to be.

We pulled into Camp 4 the afternoon of May 24. Thomas and Tony, accompanied by Jangbu, had been moving more slowly than usual and arrived an hour after Josh, Chase, Ben, and me. Camp 4 , at 26,000 feet on the South Col of Everest, is often described as one of the most desolate places on earth. It lived up to its reputation. Given that we were the only team attempting this “between cyclones” weather window, there were only two other climbers up there, which made it feel even more remote. As we threw ourselves into our tents, the clouds and wind arrived exactly as forecast. The winds increased as the afternoon progressed, and that evening Ben decided to postpone our summit attempt to the 26th.

We spent the night of the 25th and all day on the 26th in our tents: breathing bottled oxygen, listening to the wind howl, and feeling the wind violently shake our tent walls. Mid afternoon, one of our climbing Sherpas, Pema, unzipped our tent door to fill our water bottles and give us fresh bottles of oxygen. It was amazing that he could be out in those conditions. “Pema, how is it going?”, I asked. “I’m worried. The winds aren’t dropping“, he answered. I rolled back into my sleeping bag and hoped for the best.

A couple of hours later, the tent walls began shaking a bit less violently and the howls of the wind were a bit milder. We were beginning to get the drop in winds we were hoping for. Early that evening, Ben came by each tent and announced that we would go for the summit that night. The winds would be strong but, assuming we were flawless in our protection against frostbite, we should have a good chance at the summit. It would be cloudy and perhaps snowing lightly, but that shouldn’t stop us.

Because we were basically alone up there, we didn’t have to worry about crowds slowing us down, and we had the flexibility to leave whenever we wanted. Ben said we would depart sometime between 2:00am and 6:00am. He would monitor the conditions and wake us up two hours before departure.

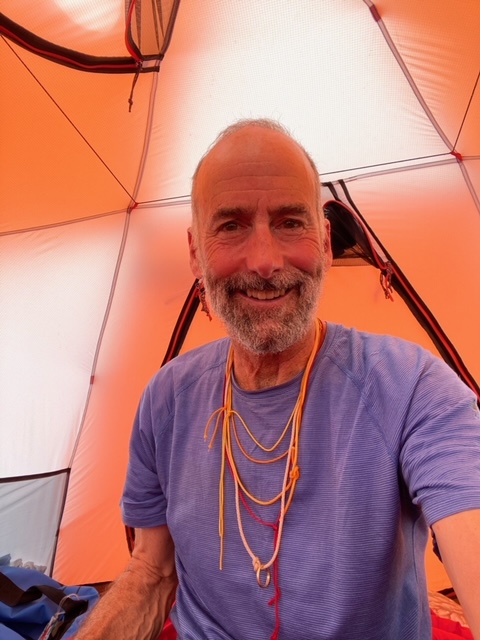

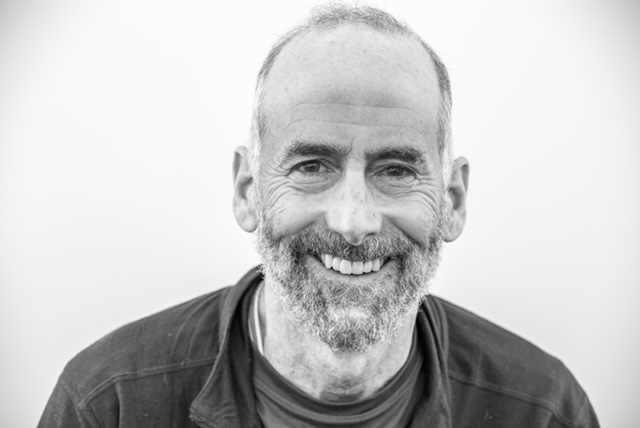

We were going to get our shot! I was elated. After so many years, I was in the position I had long dreamed of and tried to picture: in a tent on the South Col of Everest, hours from leaving for the summit. I was feeling good, was in a strong team, and in the company of the best guides and climbing Sherpas possible. And, amazingly, we would have the summit ridges to ourselves. I had no doubt I would get to the summit. Almost too good to be true. Here is a photo of me that evening about to climb into my sleeping bag, hours before “go time”:

I lay in my bag, alone with my thoughts, drifting in and out of light sleep. Around midnight, I realized that Ben hadn’t woken us up yet . The winds felt strong, but not overly so. I unzipped the tent door and noticed that snow had accumulated in our vestibule. Around 1:00am, I again realized that Ben hadn’t woken us up, and assumed that he had decided on the later 4:00am departure time. That meant we would be woken up in one hour, at 2:00am. I drifted back to sleep.

The next time I woke up, something felt weird. My internal clock sensed that a bunch of time had passed. I looked at my watch. It read 4:30 am. I unzipped our tent door and saw that our vestibule was filled with a massive snow drift. Outside the vestibule, it was snowing heavily. I shook my tent-mate Thomas awake, took off my oxygen mask so he could hear me, and said: “We’re not going!”

During the night, Ben and Jangbu had gotten out of their tent every hour to check on the conditions. The winds were in the zone we expected. The steadily increasing snowfall was not. Furthermore, it was dense, heavy snow that reduced visibility to almost zero and would make climbing exceedingly difficult. They realized they had no choice but to abort.

As day broke and it continued to snow heavily, Ben and Jangbu considered all options. They spoke with Lakpa Rita at base camp by radio and considered whether Sherpas could carry up more oxygen to allow us to wait at Camp 4 more days, for a possible last weather window after Yaas cleared out. However, the Sherpas were exhausted from weeks of carrying loads with reduced numbers, (due to accidents and illness). Even if they could get us more oxygen, a prolonged stay in the death zone would be dangerous. And what if the storm lasted more days than forecast, as Tauktae had just done, and they were unable to reach us with the extra oxygen? In that case, we would all join the ranks of statistics we had vowed not to join.

The answer was clear. We had no choice but to descend. And we had to do it immediately, in a snowstorm, before conditions got any worse. We began the multi hour process of getting ready. In a stroke of good fortune, the snowfall paused for a couple of hours, making our preparations easier. Here is a photo of us getting ready to leave Camp 4:

THE DESCENT

The descent turned out to be what you should expect, and then some, if you descend from 26,000 feet on Everest in the middle of a snowstorm.

Our initial goal was to get down to Camp 2, which meant descending the entire Lhotse face. As we left Camp 4, the snow and winds both picked up again, making walking difficult, even over the relatively level ground to the top of the Geneva Spur. We stopped at the top of the spur to wait for Thomas, who – accompanied by Jangbu- was moving more slowly than us. We waited, and waited, and waited.

What was going on? It usually takes less than 30 minutes to get from Camp 4 to where we were standing, and Thomas had started out with us. The wind and snow were whipping, and it was hard to stay warm when not moving. Finally, they appeared. Thomas was having difficulty picking his way over the rocky terrain in the snow. It was hard to believe how slowly he was moving. After more excruciating minutes, they joined us at the top of the spur.

From that spot, it is a short rappel, followed by some steep down climbing, to the bottom of the spur. I was kind of dreading it, as this would be the first tricky descending we would have to do in these conditions. Simple things, like clipping in and out of the fixed lines to move around anchor points, and braking yourself by wrapping the ice covered rope around your arms, would be far more difficult.

Ben led off. Josh, Chase, Tony, and I followed him over the top of the spur and down into the driving snow. Within 30 minutes, we were all safely at the bottom of the spur, where we stopped again to wait for Thomas and Jangbu, When we looked back up to check on their progress, we couldn’t believe what we saw.

Thomas and Jangbu were still near the top of the spur, with Thomas having extreme difficulty descending. When rappelling, his feet kept slipping out from under him, and he was having trouble moving around the anchor points. Jangbu was close behind him, assisting him with every step. We watched with concern, and also struggled personally to stay warm as we sat in the snowstorm, not moving.

Thomas reached less steep terrain and walked toward us. What shocked and horrified me was that he was still having trouble making forward progress. His knees kept buckling under him. This was the same strong climber and athlete who had been doing great the entire expedition. Meanwhile, we had been sitting in the snow at the bottom of the spur for over half an hour and were getting cold.

It was at this point that I had the realization: this is the way things can suddenly go very bad. There is a thin line between challenging climbing and a desperate situation, and we were close to it. We were at 25,500 feet, in the middle of a snowstorm, and the only people up there. There was no way we could get Thomas down unless he kept walking under his own power. He needed to keep walking. He knew it, Jangbu knew it, we all knew it.

Jangbu, as always, maintained total calm and an aura of quiet confidence, but he later told Thomas: “I was really worried for you. And I was worried for me. I would never leave you.”

In one of those seminal moments of our descent, Thomas dug deep and found the ability to get his legs moving again. Jangbu followed right behind him, supporting him with a short rope. We all proceeded down the Lhotse face, with Thomas and Jangbu falling increasingly far behind in the swirling snow, but definitely moving downward.

I turned my attention back to myself. I had to stay focused and not make any mistakes. Any time I came to an anchor point, I knew that if I failed to clip back into the fixed line properly and lost my footing, I would fall all the way down the face. Doing things properly was much more difficult in the driving snow and wind. Little things became extremely important, like making sure my goggles didn’t fog. Anyone who has hiked or skied in a blizzard can picture what I am talking about.

From our previous ascents between camps, I knew the sections I was most worried about: the steep drops and ice bulges where I would have to rappel extremely carefully. The first of those awaiting me was the yellow band. When I got there, Ben, Josh, and Chase had just finished descending it and were lost from sight in the snow. Tony was somewhere above and behind me, and Thomas and Jangbu even more so. It was one of those moments where you are all alone in a challenging situation, with no one watching or helping, and know you just have to execute. I concentrated intensely on clipping in and out of the maze of ropes dangling over the rock face, panting heavily from the physical effort. I reached the bottom of the yellow band and continued downward.

The next section that concerned me was the steep ice bulge just above Camp 3. Ben, Josh, and Chase were waiting for me there. We followed each other in rappelling down it and arrived at the cluster of tents. We were more than half way down to Camp 2!

We took what we initially intended to be a short break at Camp 3. Then Ben’s radio crackled. It was Jangbu, saying he needed some additional help and asking us to wait for him before descending further. One of our climbing Sherpas, Raj, had stopped using his glacier goggles and developed snow blindness. He couldn’t see more than a foot in front of him. In addition to helping Thomas, Jangbu was helping Raj, and it was more than he could handle on his own. So our planned brief stop at Camp 3 turned into an hour long wait.

The biggest challenge was staying warm. The winds had increased in strength and the gusts were blowing the snow sideways. After around 20 minutes, I could feel my core temperature declining and I was starting to shiver. So I dove into a nearby tent from another expedition, with my feet extending outside the door so my crampons didn’t rip the tent. It was mostly full of oxygen bottles and other expedition gear, but there was room for one person. It is amazing what a difference thin tent walls can make. Inside the tent, I was warm, and could relax while waiting for the others to arrive. Here is a photo I snapped of my view back out the tent door, with Chase and Ben staunchly continuing to wait outside:

Finally, the others arrived. I was amazed they had managed to descend the final ice wall without incident, and – credit to all three of them – they had. I got out of the tent so Thomas could get in to warm up and rest. I began to worry that he wouldn’t summon the will to emerge from the tent, but – in a second seminal moment of the descent- he did.

Then we all continued our descent toward Camp 2. Josh and Chase in the lead, then me and Tony, then Ben helping Raj with a short rope, then Jangbu doing the same with Thomas. The final challenge came at the bergschrund at the bottom of the Lhotse face, which required a lateral traverse across a narrow ice ledge, with a deep crevasse looming below. The driving snow had made the ledge even narrower than usual, and it was harder to get good purchase on it with your crampons. Also, the ice wall pushed you out away from it every time you took a step.

Josh, then Chase, then me, then Tony, all cautiously inched across it, breathing big sighs of relief when we got to the other side. Then we climbed down to where the slope eased off, and collectively looked up the face for signs of Ben, Raj, Jangbu and Thomas. They appeared first as pairs of small dots far up the face. We watched them climb down through the still driving snow to the bergschrund.

As we watched anxiously from below, both pairs slowly and carefully navigated the bergschrund, with Ben and Jangbu expertly setting up additional belay lines and providing directional guidance. Raj and Thomas inched along the ledge in turn without losing their footing. After they both got across, we knew we were in good shape. It was 45 minutes of straightforward downhill walking to Camp 2. We were safely down!

Except of course we weren’t fully down. We still had to descend the Western Cym, then down through the icefall one final time. The snow continued all night, and it was still snowing when we departed Camp 2 at 6:00 am the following morning. Instead of the usual easy downhill walk to Camp 1, we had to break trail through more than a foot of new snow. Even finding the trail was difficult; made more difficult by full whiteout conditions. With crevasses all around, and mindful that a Sherpa had fallen into one of them and died just a week ago, we had to pick our way very carefully. Ben and Jangbu did a masterful job of doing just that.

We took a break at Camp 1, then headed into the icefall, where the ice bridges were even more melted out than they had been on our ascent, the required rapells into some of the ice ravines longer, and the leaps across open crevasses more demanding. All of this was complicated by the continued snowfall, which obscured hazards and made it harder to get confident purchase with your crampons. The lower we got, the wetter the snow got. Despite having “anti- balling plates” on our crampons, the wet snow balled up under them anyway, creating inches of snow buildup that made us stumble and further eroded our ability to kick the crampon points into the ice.

Finally, we emerged out of the icefall; our sixth of six passages through it now completed. At this moment, I let myself begin to relax and thanked whoever was listening for granting us safe passage. From there, it was an easy 30 minute walk to base camp.

THE AFTERMATH

Yaas continued to pound Everest. It snowed steadily, at all levels of the mountain, for two more days. Base camp received over two feet of snow. We stayed holed up, unable to make desired connections with family and friends as the internet service was knocked out.

Several expeditions eying a post Yaas weather window have been pinned down at Camp 2. No one has been able to move up the mountain, and – increasingly- the teams at Camp 2 are uncomfortable moving down the mountain, due to avalanche risk from all the new snow. No one has summited since May 23, and it is unclear if there will be any more summits this season. This morning, we heard reports that a large avalanche down the Lhotse Face wiped out all of Camp 3, but I have yet to fully confirm this. Our guess and hope is that no one was in Camp 3 at the time due to the poor weather conditions.

This morning, the snow finally stopped. The clouds lifted, and we were able to helicopter to Kathmandu. After posting this through the hotel internet, I am about to have my first shower in a long while. Then I am going to start figuring out how to get home given that Kathmandu is in full Covid lockdown and the flights have been largely shut down. There has been some easing of this recently and I think things will work out somehow.

The past few days in base camp provided helpful time for reflection on our climb; on what we did and didn’t achieve. As I said would be the case before departing on our summit push, I really am at peace with the fact that we didn’t summit, and really do feel like I got 90 percent of the Everest experience I dreamed of. That said, the final 10 percent really hurts. We were so close, and so ready to climb the final 7-8 hours it would have taken us to reach the top of the world. Only now do I realize how much, deep inside, I was expecting to be standing up there.

I am proud of our team. We pushed right to the edge of prudent risk to set ourselves up with a shot at the summit; the only team to get up to the South Col between cyclones. When the risk became too much, we made the right decision and backed off. We then descended safely in very challenging conditions. We lived up to the quote by mountaineer Ed Viesturs that I have shared previously: “getting to the top is optional, getting down is mandatory”.

I am down, and really looking forward to coming home.

I think one final blog post, (much shorter than this one!), may make sense in the coming days. I can update you on how the final climbing days on the mountain played out, on some good team reflections after getting back to base camp, on our exodus today from base camp to Kathmandu, and a few other things.

Meanwhile, thanks for slogging through this. Happy Memorial Day Weekend to all!