Jill and I have been renting a farmhouse in Vermont this winter. It is a lovely spot and a perfect base for my Everest preparation. Here is a photo taken in early January, as the snow level was just starting to build.

I have been training hard, with a daily mix of strength workouts, long cross country skis, early morning skins up Mount Mansfield, and long winter hikes with a heavy pack. At this time of year, clear days like the one in the photo are typically accompanied by arctic cold. If you dress appropriately and keep moving, it is exhilarating to be outdoors.

Most of my training is done alone and I enjoy it. There is something spiritually meditative about moving through crystalline winter landscapes, in the company of my thoughts, maintaining a steady pace over long distances. There is also the satisfaction of feeling my body getting stronger each day, building the reserves it will draw on this spring to endure punishing days at extreme altitude.

Among my current activities, the solo winter hiking has some unique dynamics. Rock ledges that are enjoyable scrambles in summer can become serious challenges when covered in ice. Snow covered trails can be hard to follow. Straightforward ridge walks above tree line can become come life threatening when whiteouts suddenly reduce visibility to zero. The combination of sub zero temperatures and strong winds can, in minutes, turn a strong hiker into someone unable to care for themself. Cell service is often non existent. If a solo hiker slips and, for example, sprains an ankle with no one to call for help, what started out as a routine New England hike can become a serious situation.

Managing this fine line is a core element of winter hiking’s challenge and satisfaction. It has much in common with solo sailing; where every move needs to be carefully planned and executed. The details matter. Important conversations are conducted silently in the head of the practitioner. At a surface level, the hiking and sailing are routine and easily taken for granted, but the fine line lurks and commands respect.

I enjoy managing this fine line and don’t lose sleep over it. But I do take it seriously, especially when climbing the taller New England peaks alone in winter. I carefully check weather forecasts, fill my pack with backup items that are unlikely to be needed but would be critical in an emergency, and make sure someone knows my intended route and expected timing. Then I go out and rejoice in having the mountains largely to myself, confident that I have my downside covered.

This winter I have been climbing on average one large, (by New England standards), mountain a week . Targeting clear weather, I have been out often in sub zero temperatures. As long as I keep moving, take breaks at the right places, and wear the right layers, it works out great. My chosen climb this week was an extended loop over Camel’s Hump, the third highest mountain in Vermont. Careful study of the weather forecasts helped me pick a day that would be around -15 degrees F to start, warm to zero by mid day, have low winds, and remain clear through mid afternoon.

The day before Camel’s Hump, I reactivated my Garmin satellite tracking device; the one I used last year on Everest and will use again this spring. It allows other people to track my movements, and also lets me send brief outgoing text messages in places where there is no cell service. My logic in reactivating now was two-fold. I wanted to use the device a few times before leaving for Nepal, to make sure all the systems were operating properly. Also, I felt I was being a bit irresponsible this winter going on hikes without a device that could help in the unlikely event of trouble. So I went to the Garmin website, reactivated my service, and revised some of the pre-set messages. You create these messages on the website and can then send them from your device by just pushing a button.

I left the house first thing in the morning, drove to the trailhead, and was hiking as planned by 8:30am. The temperature was -12 degrees. When I felt my fingers starting to freeze, I went through the usual drill of swinging my arms vigorously to restore blood flow, then clenching them in the palm of my glove. When I felt my nose starting to freeze, I went through the usual drill of adjusting my neck gaiter to cover it. When I felt my upper body start to sweat due to the effort of carrying a heavy pack up a steep trail, I went though the usual drill of adjusting zippers to maintain temperature balance. I settled into a steady rhythm and savored the bright sun filtering through birch and pine trees. A couple of inches of fresh snow sparkled on the trail.

My plan was to do a relatively long loop up a ridge on the south side of Camel’s Hump, over the summit, and down the north side. After an hour of hiking, I arrived at a fork in the trail. To do my intended loop, I would need to take the left hand fork. I had told Jill I would only do this if the trail had been packed down by previous hikers, as I would be unable to break trail on my own with a heavy pack. It looked like one hiker had been there sometime the past couple of days. The trail was not as packed down as I would like, but I decided to give it a shot.

For the next couple of hours, I climbed steadily toward the prominent ridge. I was sinking into ever deeper snow but still able to make progress. The trail I was on gets little traffic in winter and felt remote. A different world. There was enough physical challenge to make it engaging, but not worrying. If things got tougher I would just turn around. I thought about how much I enjoyed being out there, alone, amid the beauty and silence.

When I reached the ridge, I stopped to take a short break. Here is a photo taken at my break spot, with the rocky summit of Camel’s Hump in the distance. My route would proceed through the trees, then climb up the left edge of the summit cone.

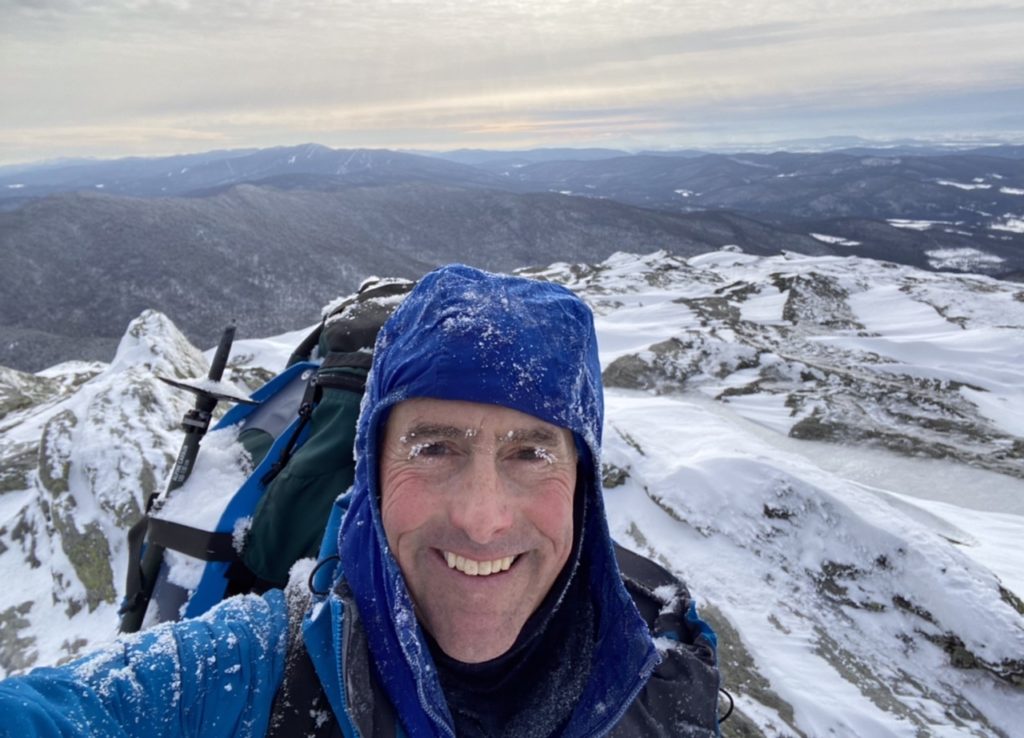

Before continuing, I called up one of the preset messages on my Garmin and sent it to Jill. I had told her I would do this, both to confirm that the hike was going well and also as a test that the Garmin messaging systems were working. Here is what I sent her:

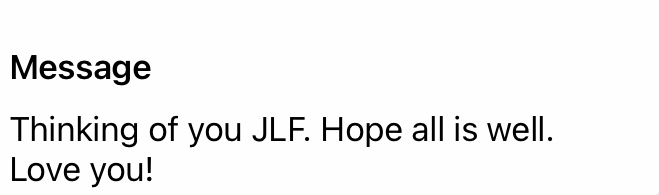

Then I kept hiking. The trail climbed steeply in places and I was glad I had my ice axe. It climbed really steeply as I approached the summit cone, breaking out of the trees onto ice-covered rock. The views west to New York’s Adirondacks and east to New Hampshire’s White Mountains were spectacular. Five hours after leaving my car, I was on the summit and feeling great. Here is the obligatory summit selfie:

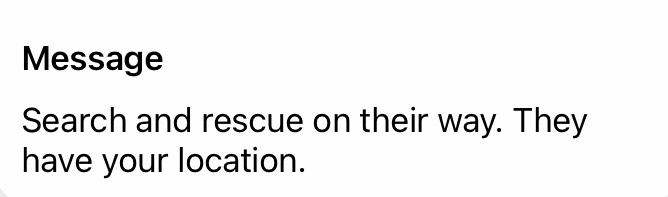

From the summit, it was a straightforward descent over the north side and down to my car. The trail on this side had seen more activity and was well packed. I moved easily and quickly. With an hour left to go, I took one last break. For the first time since sending the message to Jill, I checked my Garmin device, which was clipped to the top of my pack. To my surprise, I had multiple incoming messages. I clicked on the most recent, hoping nothing was wrong on the home front. And then things got exciting. Here is what Jill’s message said:

WHAT??????

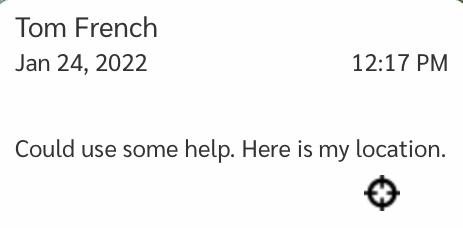

I tried to call Jill, but there was no cell service. Sending anything other than preset messages on the Garmin is tricky, but I put my increasingly cold fingers to work. After some frantic messages back and forth, the picture became clear. Garmin had some syncing issues on their server. When I sent Jill the original “thinking of you” message, this is the message she received:

In addition to the messages not synching properly, Garmin’s live tracking feature wasn’t working, so Jill couldn’t see that I had been progressing on the hike as planned. All she had was my message and the location coordinates it contained. She immediately called Garmin, trying to confirm that the message was for real, but they were unable to clarify anything. So she then did exactly the right thing and called Vermont Search and Rescue. After trying unsuccessfully to confirm whether I was really in trouble, they assumed the worst and were in the process of deploying a major rescue operation. Multiple volunteers were heading to the trailheads, and the Vermont National Guard was launching a helicopter to search the ridge.

I was mortified. Not only because of the worry I had caused Jill, but for setting in motion a massive operation that wasn’t needed. Those of you who spend time in the mountains know the extreme demands that are often placed on rescue crews. The prevalence of cell phones and other devices has increased the number of distress calls that these crews receive, often from people who don’t really need help or shouldn’t have put themselves in the situation in the first place. There is a growing movement, which I support, to charge people for the costs of these rescues. I wondered how many people had been deployed on my behalf, and began mentally preparing to write a large check to the state of Vermont.

All’s well that ends well. Jill got to the National Guard just in time and the helicopter never took off. The search and rescue volunteers were told to turn around. I kept walking down the trail. Upon arriving at the trailhead, I encountered two men in full winter gear with radios on their chests. “Hi”, I said, “I am the idiot who just messed up your day”. They could not have been more gracious. “No problem”, they answered, “we are just glad you are ok”.

Equally gracious was Neil Van Dyke, the head of Vermont Search and Rescue, who debriefed me the following day. It was Neil who had calmly talked Jill through the situation while my status was unclear, and who assumed responsibility for deciding to deploy rescue resources. Ever the professional, Neil wanted to understand the exact sequence of events, with an eye toward continuously improving future decision making. It was comforting when he pointed out that I had done nothing wrong. I pointed out the irony that, in trying to be extra safe and careful, I had inadvertently launched a major rescue operation.

So, in addition to there being a fine line between a routine hike and a dangerous situation, there is a fine line between devices that can save you in those situations and devices that can marshal rescue resources unnecessarily. I have since figured out what happened on Garmin’s end. I don’t blame them. You could argue that it was my fault, and my device is now working perfectly. I am left with a sheepish realization that I inadvertently mismanaged a technological fine line. More profoundly, I am left with deep respect and gratitude for Vermont’s Search and Rescue community and their peers in other states. I hope never to really need their assistance but is comforting to know they are there; for me and others like me.

Meanwhile, my training continues and I have more solo winter hikes to look forward to. Time is flying. I leave for Nepal in less than two months.