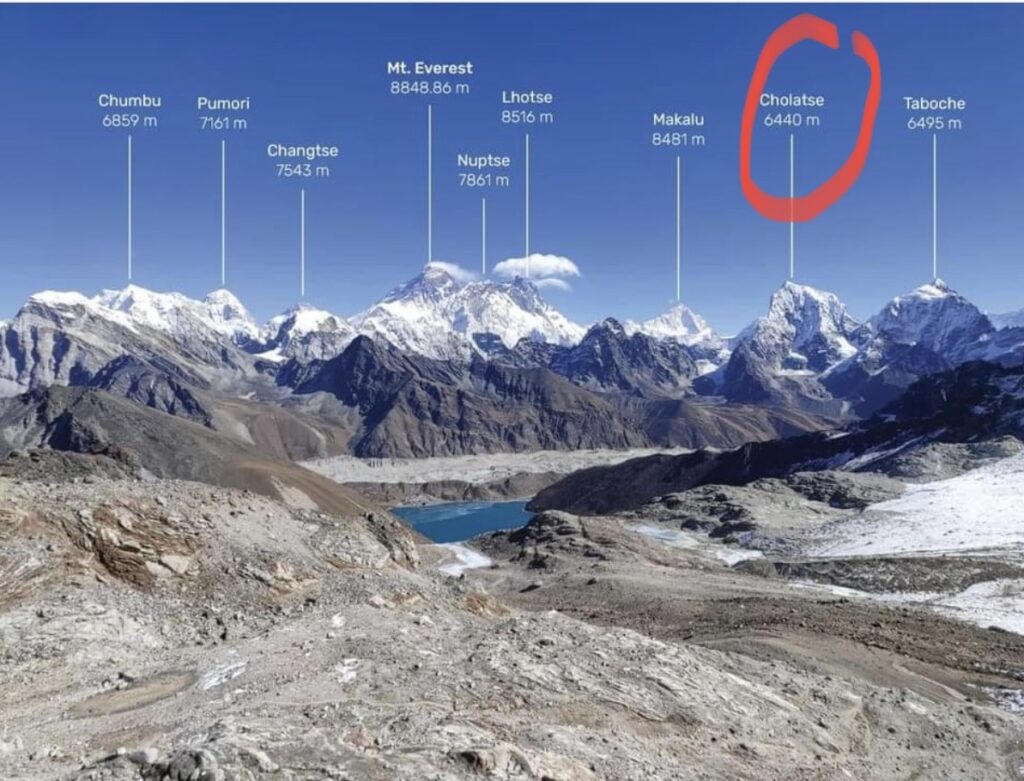

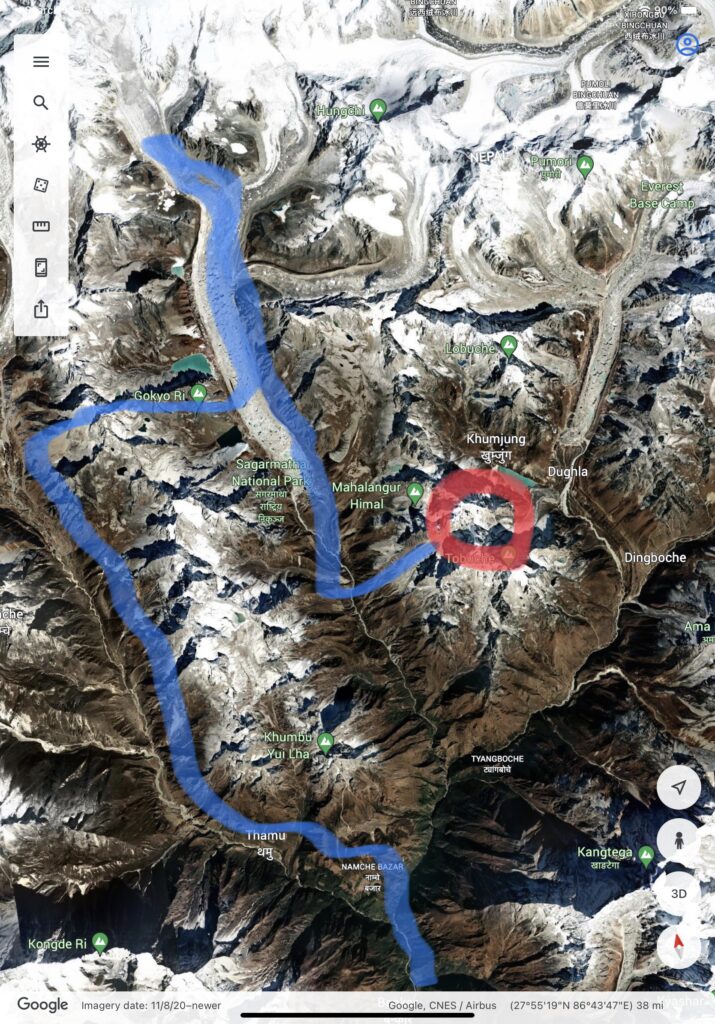

I am now back in Kathmandu. When I last posted on November 7, Holly had just left the Cholatse expedition and the rest of us were gearing up for our attempt on the summit. In a typical component of high altitude mountaineering, we were eying the weather forecast waiting for the winds to drop. It looked like there would be a 24 hour weather window on November 12, and – with every passing day – the forecast continued to hold up. We just needed to wait patiently.

As I mentioned in my last post, I had more than the usual pit in my stomach as I looked up at the mountain from base camp. Cholatse is steep, challenging climbing, with knife edge ridges and several thousand foot drops on all sides. This year, there were indications that it would be more challenging than usual. Climbing those ridges depends on ascending ribbons of snow and ice that sit above the rock layer, and – in a pattern that is repeating itself on mountains worldwide – climate change is causing Cholatse’s snow and ice to recede. Additionally, this was an unusually low snow year in the high peaks of the Everest region. Teemu, the Finn who I was on Everest with in 2022, led a climb on a nearby peak earlier this fall, and warned me in an email to “expect a lot of rock”.

There were other indications that Cholatse would be challenging. Shortly before we arrived at base camp, a highly accomplished Czech climber fell to his death while climbing the same route we would be on. He did so while climbing “alpine style”; not clipped into a fixed rope. While we took comfort that we would be using fixed ropes on the entire upper mountain, these ropes can only do so much for you. If you fall, you can drop a long way before they catch you, and every time you clip in and out of them you risk that you don’t re-attach yourself properly. As Phil, our expedition leader, repeatedly stressed, “On Cholatse, if you fall when not clipped in correctly, you are going to die.”

In another unsettling indicator, a pair of climbers who reached the summit a few days after we got to base camp took a shockingly long time to descend. We stood outside the dining tent after dinner and watched small points of light of their headlamps as they rappelled down the treacherous final ridges to Camp One well after dark. Had they not left early enough on their summit push, or was there something else going on?

While I wasn’t overly freaked out, this all weighed on my mind. While Everest was exceedingly challenging physically, and had its tricky moments technically, most of the risk lay in how my body handled the altitude, and in whether or not an ice block in the Khumbu icefall collapsed as I happened to be passing through it. Otherwise, I just had to keep putting one foot in front of the other, day after day, and maintain my mental strength. On Cholatse, especially this year, I felt I would be stretching myself on dimensions of my technical climbing skills. I have long believed that, in the mountains, you need to heed your inner voice. Holly had listened to hers. Mine was at least raising the question of whether I should continue with the climb.

To center myself, I broke down each stage of the summit route in my head and pictured how I would handle it. I reminded myself that I was part of an extremely well-led and supported team, and that I just needed to execute properly. The fact that my climbing partner would be Sonam, one of the Sherpas with whom I climbed to the summit of Everest, was immensely reassuring. He is extremely competent, detail oriented, and we have good rapport. If things started to feel out of hand up there, I would just turn around.

The day I hiked from base camp to a nearby village to transmit my last blog post was also very centering. I walked up a long valley beside a glacial moraine, through grassy meadows surrounded by towering peaks, enjoying the simple rhythm of walking through beauty. During the five hour round trip, my only encounter on the trail was with a yak herder and his yaks, their bells jingling. On the return trip, the upper portion of Cholatse was constantly in front of me, rising above the hills and meadows. Despite my worries, I was glad I was headed there. Here is a photo I took as I walked past some yak enclosures.

Back at base camp, the weather forecast continued to tighten around the 12th being our day. Winds which were blowing at 40-50 mph across Cholatse’s upper ridges were expected to drop to 10 mph for a 24 hour period. We would head back up to Camp One on the 11th. As the time approached, my team members were managing their own emotions. Lenny, who has climbed some challenging peaks in Peru and soloed 23,000 foot Aconcagua in Argentina, said unequivocally: “If this weather window extends any further, I am out of here. I can’t stand the waiting.” Martin, who has climbed extensively in the Alps and last year summited nearby Ama Dablam, reflected: “Things feel different. Maybe it’s my two young daughters. I am just less dialed in.” Dan, the youngest on our team, and also an accomplished climber, said: “For me, there is always this anxiousness before a climb. I’m not sure how I will do up there, but I’ll give it a shot”.

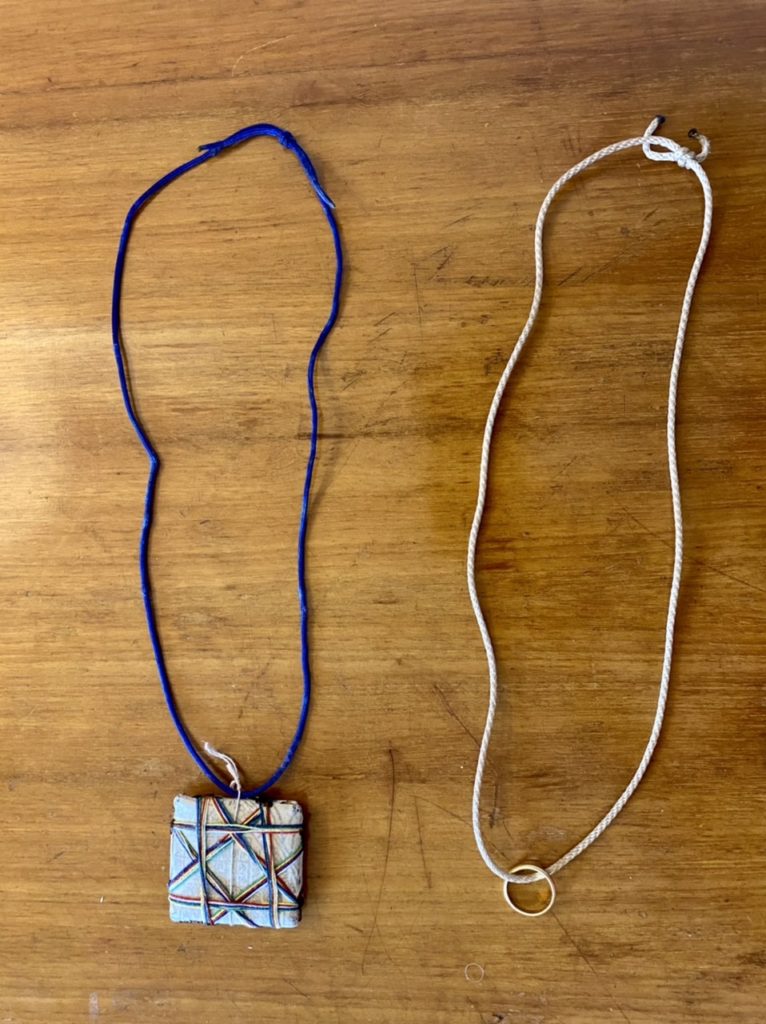

The morning of the 11th, we methodically filled our packs, triple checked that we had every item on our checklist, and prepared to head to Camp One. As we left base camp, the Sherpas burned juniper at the alter which had been blessed by a local lama when we first arrived at the mountain. As is his custom, Phil let each of us move to Camp One whenever we wanted, free to move in company or alone as we preferred. I climbed alone, and felt great every step of the way. Physically, my body had adjusted to the altitude and I felt strong. Mentally, something had clicked to make me feel confident and ready. Half way up the steep headwall from the glacier to the saddle where Camp One is located, I clipped into an anchor point on the fixed line, paused, looked around, and felt an unexpected wave of pure contentment. By the time I pulled myself over the top of the headwall, the usual afternoon clouds had closed in on Camp One, but it still felt good to be there. Here is a photo I took as I arrived.

Phil had decided on a 1:00am start, which I totally agreed with, especially as he wanted us to climb from Camp One all the way to the summit, (passing but not stopping at Camp Two), and then descend all the way to base camp in one long day. We would climb by headlamp for 4-5 hours, be on the summit ridge by daybreak, and have plenty of time to reach the summit and get down off the steep sections before dark. We had an early dinner, lay in our sleeping bags, and tried to get some sleep. Dan and I shared a tent. At 11:30pm, my alarm went off and I began my preparations. Martin called out from the tent next to us: “I’m not feeling good. No summit for me. I’ll head down to base camp when it gets light. Good luck guys!”

At 1:00am sharp, Sonam and I crossed the snowy shelf to where the fixed lines started up a steep rock band, and began climbing. As I had been moving faster than the rest of the group during our time on the mountain, Phil had determined that we should go first. The others followed. The rock band above Camp One is notorious for being some of Cholatse’s toughest climbing. The first part is close to vertical, with zero snow or ice for your crampons to gain purchase on. For purists climbing without fixed lines, (like the Czech who fell to his death from here), this requires paramount technical skills. For the majority of us who use fixed lines, it is more an exercise in brute strength. You attached your ascender device to the line and haul yourself up with your arms, crampons scraping on bare rock for foot purchase. I had mentally rehearsed this part, so I was prepared. It was hard work right out of the chute, but went as expected.

The route then moved to the other side of the rocky knife edge edge and worked its way upward at a more gentle angle. This also went as expected. Phil’s advance description of this portion: “It is great that we climb it at night, because you can’t see the drop below you. When you descend it later in daylight, you will be terrified.” After an hour of climbing, Sonam and I reached a notch where the route moved back to the other side of the ridge. Typically, at this point it would turn to snow and the climbing would be more straightforward. This year, however, the ridge remained mostly rock. We traversed a thin snow band under the ridge edge, (with me remaining grateful I couldn’t see what was beneath me). Then the route climbed vertically back to the top of the ridge, and was all rock. This was unexpected, and required 20 minutes of hauling ourselves up the fixed line with our ascenders, legs frantically trying to gain some form of crampon purchase. Several times, I felt my arms failing and wondered if I could get up it. Finally, I did, and mentally thanked the upper body strength training I had continued post Everest.

Shortly after the vertical rock section, the ridge turned to all snow and continued upward. While longer, steeper, and much harder work than I had mentally pictured, it was in the realm of the doable. I would make about ten steps, stop and take prolonged gasps for air, take another ten steps, and stop again. It was hard enough that I began to wonder if I should turn around. I don’t recall ever having had this level of doubt on a mountain before. I kept going, looking for the small indentation in the ridge where Camp Two is typically located, as a marker of progress. But it kept not appearing. At this point, flexing his super-human mountaineering speed, Phil had climbed ahead of the group. He had noticed that a number of the fixed line anchors were insecure and wanted to strengthen them where needed.

Four hours into the climb, it began to grow light on the horizon. I was dimly aware of surrounding summits being illuminated in the pre-dawn light, and dimly aware of the beauty of the moment. The ridge flattened briefly and I asked Sonam: “Is this Camp Two?”. “Camp Two already below us”, he responded. I had missed it in the dark. We climbed higher, and reached the point where the angle of the ridge eases. It was now fully light and we switched off our headlamps. I knew from here it should be a few more hours to the summit, on far more gentle terrain, and I began to think I might make it. I dug my camera out of my down jacket and took this picture of Sonam.

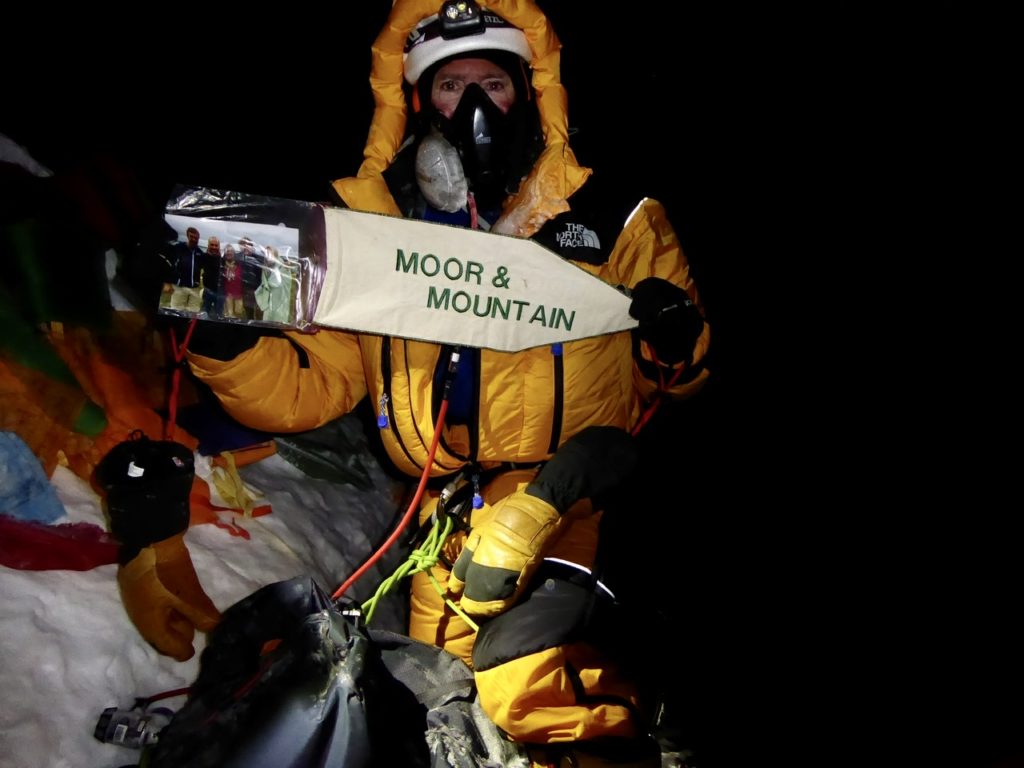

Meanwhile, Sonam checked in with Phil and the other Sherpas on the radio. “Lenny and Dan turn around”, he informed me, “now just you.” We continued. In the distance, we could see Phil climbing a steep ramp to what looked like the summit. It was further away than I wanted it to be. We continued. Some time later, Phil passed us on his way down, having reached the summit. I guessed it was maybe thirty minutes away. “You are doing great”, he encouraged us, “only an hour to go.” So much for thirty minutes. We continued. We climbed the steep ramp I had seen Phil on and I knew we were close. Then we reached a level section, the so-called “false summit’ which many people define as close enough to the actual top. “You want go to true summit?”, Sonam asked. I responded: “You think I can do it?”. He nodded yes. Getting there involved surmounting a thirty foot vertical wall of ice, but that was relatively straightforward given the fixed line and solid ice to kick our crampons into. Then all that was left was a short, gentle climb to a broad, snow covered apex. At 8:30 am, we were on top of Cholatse, in bright sunshine and no wind, with stupendous views in every direction. I saw Gokyo, from where I had viewed Cholatse on my approach trek. Here is a photo Sonam took with my camera. Loyal readers of this blog will know that I have carried the same banner to the top of multiple peaks. Everest was one of them. You can see it’s summit pyramid behind me in the upper right corner.

Perhaps even more than on Everest, I was mindful that the summit was only the half way point. We started down, making good time on the upper, gentle ridges. Then we started a long series of rappels down the steep snow ridges. I kept repeating the same mantra I used when descending Everest: “don’t mess up, don’t mess up”. (The word I uttered was a different one than “mess”.) At every anchor point, I focused maniacally on what I was doing, and Sonam checked every element of my setup. He is the same age as Holly, but in this relationship he acted the father and I the child. We continued descending.

I dreaded the final rock sections above Camp One, but they actually went better than I had feared. I focused intently on every micro movement, and was largely able to ignore the thousands of feet of air beneath my feet. I didn’t like it, but I was able to keep moving. The biggest challenge was exhaustion. I was close to fully spent, which made concentrating even harder. At 3:00pm, we rappelled down the final rock slab and arrived back at Camp One, which was mostly deserted as the rest of the team, having aborted their summit climbs, had packed up and headed down to base camp. I longed to crawl into my tent and collapse, but knew that wasn’t an option. Pasang Nima, (another one of the Sherpas I was on Everest with), offered me half a bottle of Coke as he prepared to depart camp. I accepted gratefully. Sonam packed up the one remaining tent, (while I watched him do all the work), and shortly after 4:00pm we lowered ourselves over the headwall lip and rappelled down to the glacier.

I knew our final descent would be physically miserable, but also knew I could do it. We descended to the foot of the glacier, removed our crampons, and traversed the insufferable rocky moraine. Our final hour was in the dark, headlamps back on. My mind began floating away from my body, as sometimes happens at high altitude, but this time is wasn’t the altitude. Finally, I could see the lights of our base camp tents below us. Shortly before 7:00pm, we were back.

We received a warm welcome from Phil and the rest of the team. Dinner was about to be served. I said I would be late, as I needed to send a satellite text message to my family, telling them I was down safely. I also needed to change clothing. I had on the same layers I wore to the summit, and on the lower descent they had become sweat soaked. Fifteen minutes later I was back in the dining tent. Phil reflected on the day. The mountain, due to the changed snow conditions, had been far more challenging than when he was last on it in 2019. “I’m not sure I will be back again”, he said. “Despite the high level of experience in my clients, Cholatse is now at a level of difficulty beyond where most of them should be.” He went on to comment on Cholatse relative to Ama Dablam, the nearby mountain widely viewed as a signature climb with technical intensity: “Cholatse used to be a bit harder than Ama. Now it is orders of magnitude harder.”

As desert was served, I felt a chill coming on and couldn’t shake it. I started shivering uncontrollably. I said good night and headed to my tent. The shivering was so intense that I had trouble opening the tent door. Finally, I succeeded, crawled into my sleeping bag, warmed up, and fell asleep.

I woke up the next morning to this view: Cholatse viewed through the prayer flags of our base camp alter.

I have written in the past about Type 1 and Type 2 fun. Type 1 is the kind where you are having fun in the moment: like when you are walking in a park with a friend or having a picnic in the sun. Type 2 is where you are miserable in the moment, but – with the passage of time- what you did becomes deeply satisfying. Mountaineering involves a lot of Type 2 fun. Everest is virtually all Type 2 fun. I was physically miserable on it much of time and thought it would always be my high water mark for Type 2. Now I’m not so sure. The 18 hours between when Sonam and I started climbing from Camp One and when we arrived back at base camp was pretty much pure misery. Most of the time, I questioned why I was doing it and wondered if I should turn around. Holly had decided that “the satisfaction I received from summiting wouldn’t be worth the suffering involved in getting there”, and I reflected on whether that was true for me. My initial inclination was that it was: due to a combination of the physical suffering and the level of risk that turned out to be involved.

But my feelings evolved, even over the course of my first day back. By mid-day, I was looking up at the summit ridge and feeling a deep sense of satisfaction. Also the same feeling I had on Everest of having travelled to a spiritual, far away place and returned changed for having been there. That afternoon, as we sat on our duffle bags in the sunny meadow of base camp waiting for a helicopter pickup, I felt deep contentment. The helicopter arrived just in time before afternoon clouds pinned us down in base camp for another night. After a refueling stop in Lukla, the chopper took us on to Kathmandu. As we flew over ridge after ridge with the sun piercing the cloud layer, I thought of the deeply meaningful trips I have made in this country over forty years and how grateful I was for this one. As I have done each of the past three years, I returned from the mountains to the Yak and Yeti hotel and had one of the longest, best showers of my life.

Holly was still in Kathmandu. She joined us for a team celebratory dinner. Then today she and I had a long lunch, trading reflections on Cholatse. I congratulated her again on making a mature, right decision; even more right given what played out on summit night. She knows that she did. Her inner voice was remarkably clairvoyant.

As for me, I don’t want to climb another mountain like Cholatse, but I’m glad I climbed this one. I wasn’t sure I would climb any big mountains after Everest. Despite pushing the envelope, Cholatse took me to new places that I am glad I got to experience. I am deeply grateful. As I advance into my sixties, I expect I will find different kinds of places, hopefully equally meaningful.

I fly home tomorrow night. It will be great to be back. Heartfelt thanks for being part of my journey.