Greetings from base camp as we continue to wait for the optimal weather window to try for the summit. We are getting close. This post is a grab bag of various topics.

WAITING AT BASE CAMP FOR THE WEATHER WINDOW

As described in my last post, we are following a “go late” strategy, meaning we must not only wait for a weather window, but also – if possible- have the patience to sit tight and let other teams go for the summit ahead of us, hoping for an even later window more to ourselves.

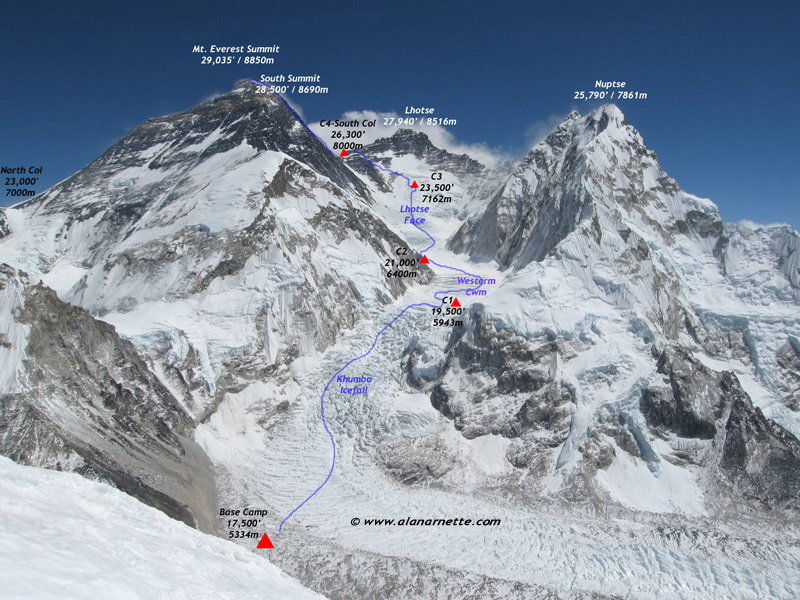

As expected, it looks like the next good window will be roughy May 19-22. As it takes around six days for an acclimatized team to get from base camp to the summit, this means that a number of teams pulled out of base camp this weekend to head up the mountain and get in position for their summit bids. It is really hard to sit here and watch them go, particularly as there aren’t too many climbing days left in the season, but that is what the “go late” strategy is all about.

We are hoping/betting that, after the majority of teams who are left on the mountain take their summit shots around May 19-22, another window will open up before the end of the month. Most years it does. If it does again this year, we may end up realizing our dream scenario of having the upper mountain largely to ourselves. That is what we are waiting and hoping for.

It is hard to be patient in this situation, but base camp is a pleasant place to wait. During the day, when the sun is out, it is positively warm. Evening temperatures drop down to the low teens, but our sleeping bags are warm and our acclimatized bodies sleep soundly at 17,500 feet.

Here is a photo of our team during one of my favorite times of the day: sipping coffee outside the dining tent before breakfast, relishing the early morning sun on our faces and the mountain views. Ben and Lakpa are in the background.

Today, in the interest of staying physically sharp, we went on a hike across the Khumbu glacier to the other side of the valley. It was gorgeous, and going on a relaxed hike as opposed to gasping for air higher on the mountain made it particularly easy to look around and savor being in such beautiful surroundings.

Years ago, the original Everest expeditions had their Camp 1 location further up on this side of the valley, and we had fun playing “amateur archeologist”; looking for artifacts from the original expeditions that the glacier had carried down the valley. We were like little kids on a treasure hunt, and were delighted when we found several tent pegs, a bit of climbing rope, and a couple of sardine cans. Chase also found a circa 2010 Srixon golf ball, for which we have no historical explanation. Here is a photo of our ace archeological team in action:

In the coming days, we will stay committed to a mix of waiting patiently and going on hikes to stay sharp. If I had to guess, I’ll bet we head back up the mountain within the next three to four days, eyeing a summit attempt around May 25-27. It all depends on the weather, which we fervently hope breaks favorably for us. Stay tuned.

THE COVID SITUATION

Nepal continues to experience a really nasty Covid surge, connected to a horrible surge in neighboring India. With very low vaccination rates and limited healthcare infrastructure, I really feel for the country, especially the densely populated areas such as Kathmandu and its outlying villages.

Meanwhile, despite what the press would have you believe, the Covid situation at base camp and on the mountain feels very manageable. Not without challenges, but manageable. The reality is that each expedition has its own base camp area, entirely removed from the others. Once on the mountain, people move very independently, outdoors in the extreme, with various forms of climbing- related masks on their faces. The risk of Covid passing between members of different expeditions is effectively zero.

So the issue comes down to how well each individual expedition manages its Covid risk, (and how lucky/unlucky they are). In our small team of five climbers and two lead guides, with the best base camp manager in the business, (Lakpa Rita), things are very tightly managed. Effectively all of us western climbers are vaccinated, the climbing Sherpas are strongly encouraged to social distance and are tested frequently, and we operate as a totally independent pod, never mingling with other teams. We feel totally safe.

Some other teams have not been so fortunate, especially larger teams, with some of their climbing Sherpas and members testing positive and being evacuated/removed from base camp.

Some of you may also have seen some Everest-related announcements from the Chinese government. A week ago, they announced that they would install a barrier to prevent Nepal-side climbers from crossing to the China side of the roughly 20’ x 20’ shared summit and spreading Covid. Everything about this announcement was absurd, starting with the idea that such a barrier could be erected or enforced on a tiny mountain summit at 29,000 feet, and ending with the idea that small numbers of climbers wearing oxygen masks represent a health risk to each other. Then, several days ago, in an equally absurd announcement, China cancelled the one, (Chinese), expedition they were allowing on the north side of the mountain this year, citing the same concern for Covid exposure on the summit. Clearly, China is attempting to use Everest to promote a broader narrative of “Covid responsibility” to the world community. I wish they would resort to more fact-based methods.

To return to more practical Covid matters, and to summarize : I worry greatly about Covid’s impact on the broader Nepalese population, but worry very little about its impact on our team’s ability to climb the mountain safely. I do worry about its impact on our ability to get home after we get down, as all domestic and international flights in Nepal currently are shut down. But we will deal with that when we get there. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

ANSWERS TO SOME QUESTIONS YOU HAVE ASKED:

I apologize for not addressing many of the great questions some of you have asked, but here are answers to a few:

Trash on the mountain:

I honestly see very little trash or other degradation, with the overwhelming impression being a pristine, beautiful mountain environment. Base camp in particular has surprised me with how orderly and clean it is. Higher on the mountain, the biggest annoyance so far is occasional throat lozenge wrappers that Sherpa teams drop on the route. It is true that, in some places on on the upper mountain, human waste, after being carefully bagged, is thrown into deep crevasses, but this is a practice observed on a number of the world’s tallest mountains. It is also true that, when I am at Camp 4 at 26,300 feet, I expect I will see discarded oxygen bottles, frozen human feces, and more than one frozen dead body, but this doesn’t surprise me given the extreme nature of that environment and how challenging it is to function up there.

In summary, while the environmental challenges the press writes about are real and to be taken seriously, I am experiencing a very different – and much more positive – situation than the “Everest has been irrevocably trashed” narrative. This mountain feels to me like a wild, beautiful, awe inspiring environment, where nature rules.

Temperatures and wind speeds:

In the upper camps, temperatures drop well below zero at night. When (if) the sun hits, things warm up rapidly. On our climb from Camp 4 to the summit, we are expecting nighttime temperatures around -30 F, and daytime temperatures still well below zero.

Wind speeds when the jet stream is on the summit can range from 40 mph to 100 mph. When the jet is off the summit, climbers are hoping for winds below 30 mph. An ideal summit day might be 10 mph.

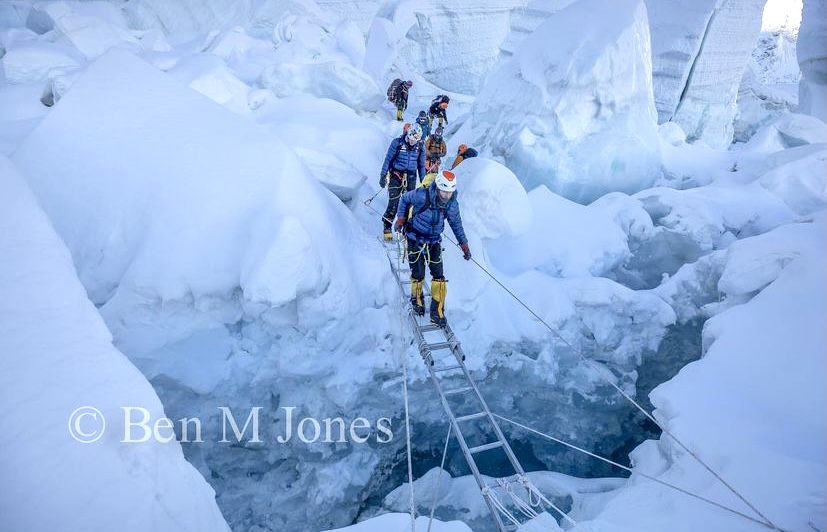

ICEFALL PICTURES FOR THE FUN OF IT

As discussed previously, every trip through the icefall is simultaneously nerve wracking and beautiful. It is a constantly shifting maze of huge ice blocks, ridges, ravines, and deep crevasses. In a number of places, ladders are stretched across crevasses and the trick is to walk across them without your crampons getting caught in a rung, and also without looking down into the crevasse and thinking too much.

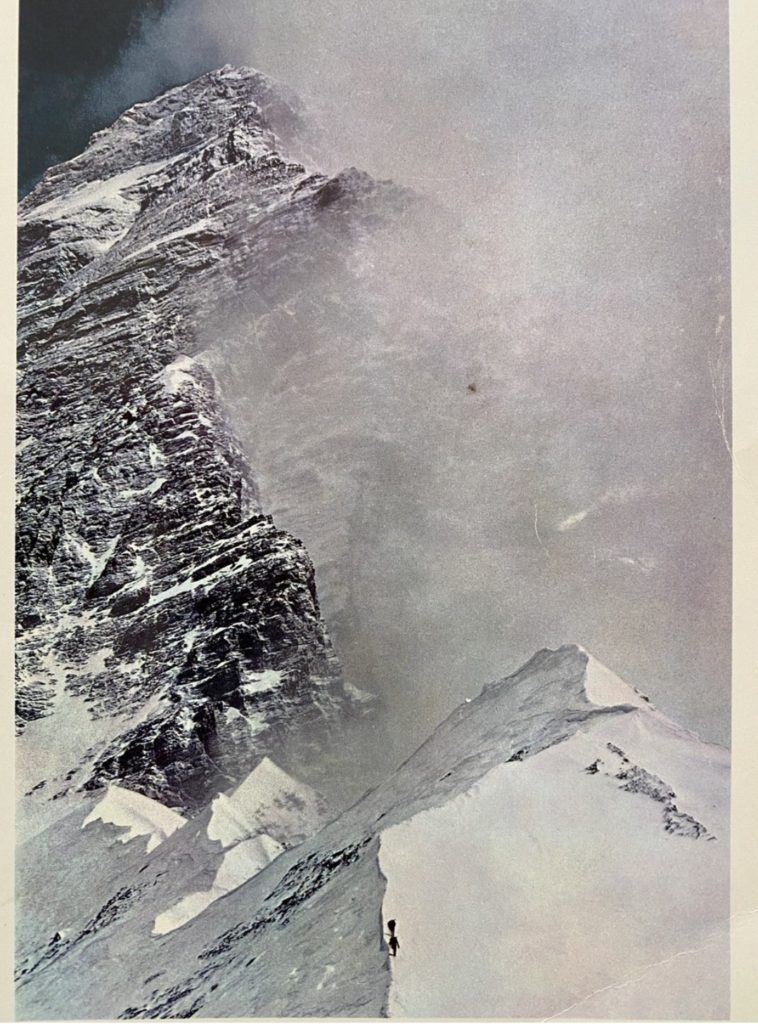

Here is a photo Ben took of me on our descent through the icefall on our second rotation; traversing an ice bridge:

And here is another one of me crossing a ladder:

As mentioned previously, we will pass though the icefall a total of six times on this climb, (three up, three down). Four of those passages are already behind us. For me, regardless of what does or doesn’t happen on summit day, the climb won’t be over until I emerge out of the bottom of the icefall that sixth time.

WHAT I WILL CARRY TO THE SUMMIT

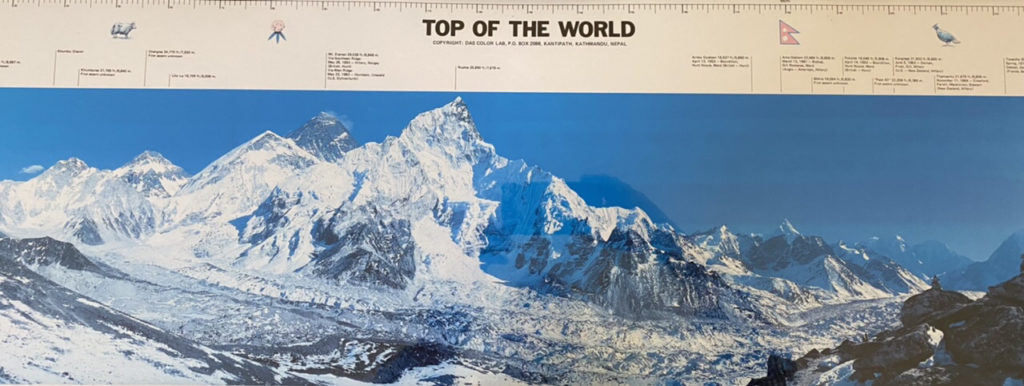

Here is a photo of what I will carry in the top of my backpack on our final climb , and what I hope to unfurl on the summit:

“Moor and Mountain” is the name of the camping and climbing equipment store my father owned when I was growing up; where I sat on the floor as a young child reading books about the epic climbing expeditions of the 1960’s and 70’s. The store closed almost 20 years ago, but a number of you have been there and remember it.

In 1992, when I climbed the West Rib of Denali with friends Matt, Colin, and Bob, Moor and Mountain was our go-to equipment supplier, and we carried a Moor and Mountain flag to the summit as thanks. Over the past several years, I have carried the flag to the summits of Ranier, Vinson in Antarctica, and Aconcagua.

The flag represents a number of things to me: the store’s enduring gift of a love of the outdoors, it’s role in inculcating the romance of mountaineering, and – in a different vein- the grace and nobility with which my father managed the enterprise through its various ups and downs over the years. Given how strongly our family was intertwined with Moor and Mountain, the flag also symbolizes my gratitude for the family that raised me, and my love for my father, mother, sister Cathy, and sister Hilary. Every time I have unfurled it on a mountain summit, I have gotten surprisingly emotional.

The photograph is of Jill, John, Holly, and Will, (and me), on Jill’s and my 25th wedding anniversary. It needs no explanation. These four individuals are the core of my universe. They make my every step on this planet meaningful, and they are with me every step of the way on this climb. I would like so much to carry their images to the top of the world.

Note: the photograph was expertly attached to the flag in my tent today, through deft wielding of a Swiss Army knife and dental floss.

THE IMMEDIATE FUTURE

We will keep our eyes on the weather forecast, stay patient, and hopefully head up the mountain within three or four days. I’ll post one more time before we leave, with final details.